Tawi–Tawi has now become part of our core memories. From the moment we arrived, we already felt a sense of profundity in what lay ahead, and we were right. Every place we visited evoked a keen sense of humanity that is one with the cosmos: from the pristine beaches of Panampangan and Sangay Siapuh evoking the vastness of space, the archaic caves of Balobok evoking the infinity of time, and the spirituality of Simunul and Bud Bongao evoking the divine.

Who ever said that all good things must come to an end? What was he thinking?

Well, the Tawi–Tawi experience might have ended, but the memories it imprinted upon us would be hard to end remembering. Besides, there are still more in store for us in our pilot adventure in Mindanao.

Photo mix: from Sanga–Sanga Airport in Tawi–Tawi back to Zamboanga International Airport.

Roughly around an hour after we left Tawi–Tawi, we were back in Zamboanga City, the place where our Mindanao adventures started. Our service vehicles were waiting outside the airport. Yes, vehicles, as two service vans would be taking us around the landmass of the Zamboanga Peninsula. Before we went anywhere else, the group first went to the accommodation that would house us for the night so that we may first unload our things. As soon as that was in order, we headed to Paseo del Mar where we will be having our late lunch.

Yes, Paseo del Mar, the premier park of Zamboanga City lined with restaurants that we visited during our first day in Zamboanga City. We were back there for lunch, which we had at Mamang’s Greasy Spoon. Though we were with the Aura Adventures gang, we got to order on our own. Ran and I chose two dishes that are well known in the local cuisine, pyanggang manuk for our main and knickerbocker for desert.

Pyanggang manuk and knickerbocker.

When we were in Paseo del Mar three days earlier, we did not really explore the area, knowing that it was included in the official tour itinerary after all. Hence, as soon as we finished our lunch, Ran and I bolted out from the group. Not that we were not enjoying the meal and the company we were surrounded with, but the goal in mind was clear: explore the historical site that is adjacent to Paseo del Mar.

The journey back in time once again began.

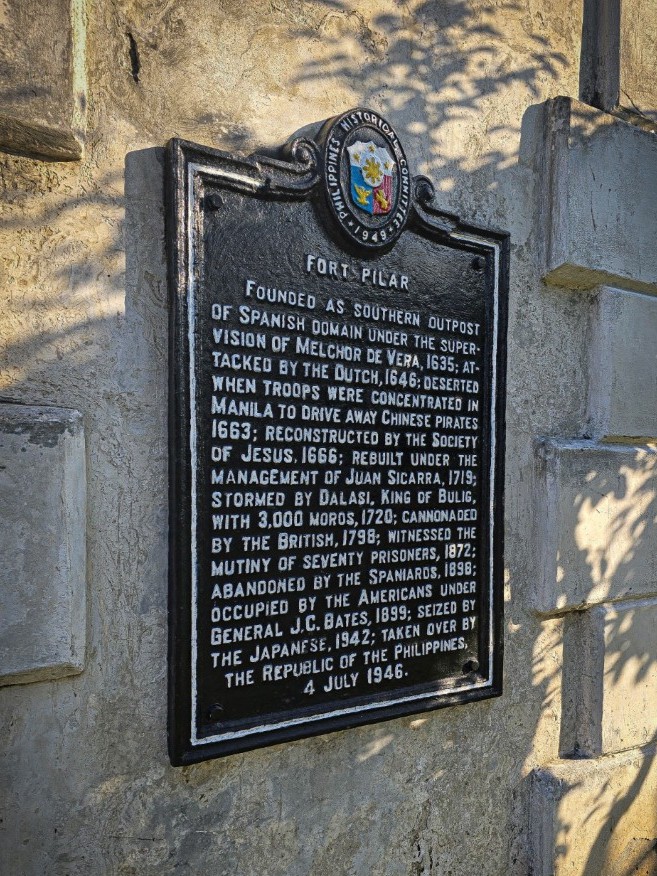

Picture this in sepia. The year was 1635, and the Jesuits together with the Bishop of Cebu requested that a stone fort be built by the sea. The cornerstone was laid on 23 June 1635, and with the building of a fortification of mortar and iron, a city was born. The date of the cornerstone laying is also considered as the foundation day of Zamboanga.

Originally named as Real Fuerte de San José, the fort was built in order to repel pirate and Moro attacks, and invasions from the Dutch, Portuguese and British—such an irony of invaders repelling invaders. The fort was rebuilt in 1718 and was renamed as Real Fuerte de Nuestra Señora del Pilar de Zaragoza, in honor of the popular apparition of the Virgin Mary that is also considered as the Patroness of Spain.

The entrance to and the historical marker of Fort Pilar.

Still standing strong to this day, the fortification that was built to keep people out is now one of the most welcoming sites in Zamboanga City. Since the National Museum took over its administration in the 1980s, it has become a place where fortification of knowledge constantly happens in its exhibition of the rich natural resources, culture, arts and history not only of the Zamboangueños but of the historical Moro Province at large.

The courtyard of Fort Pilar.

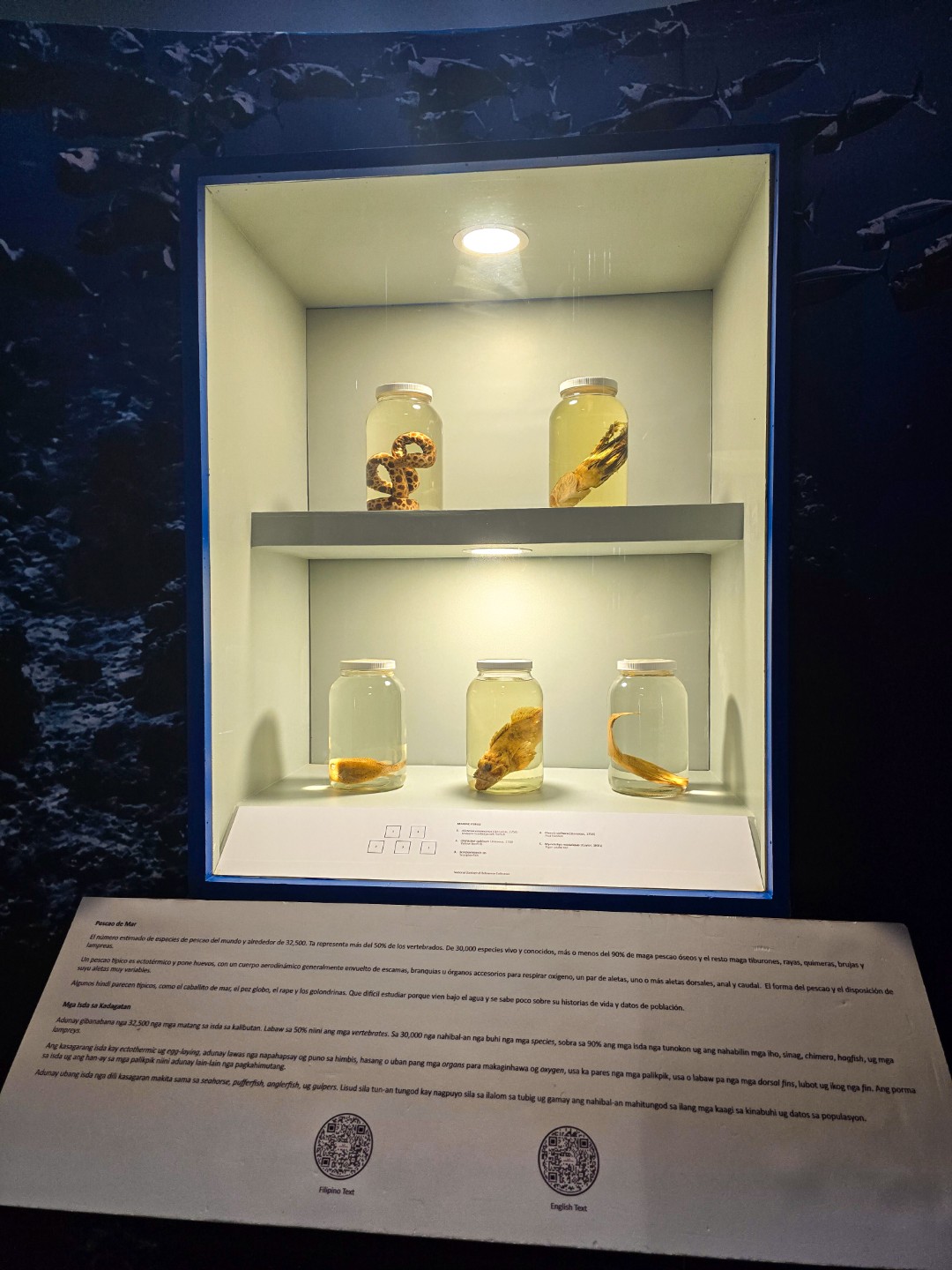

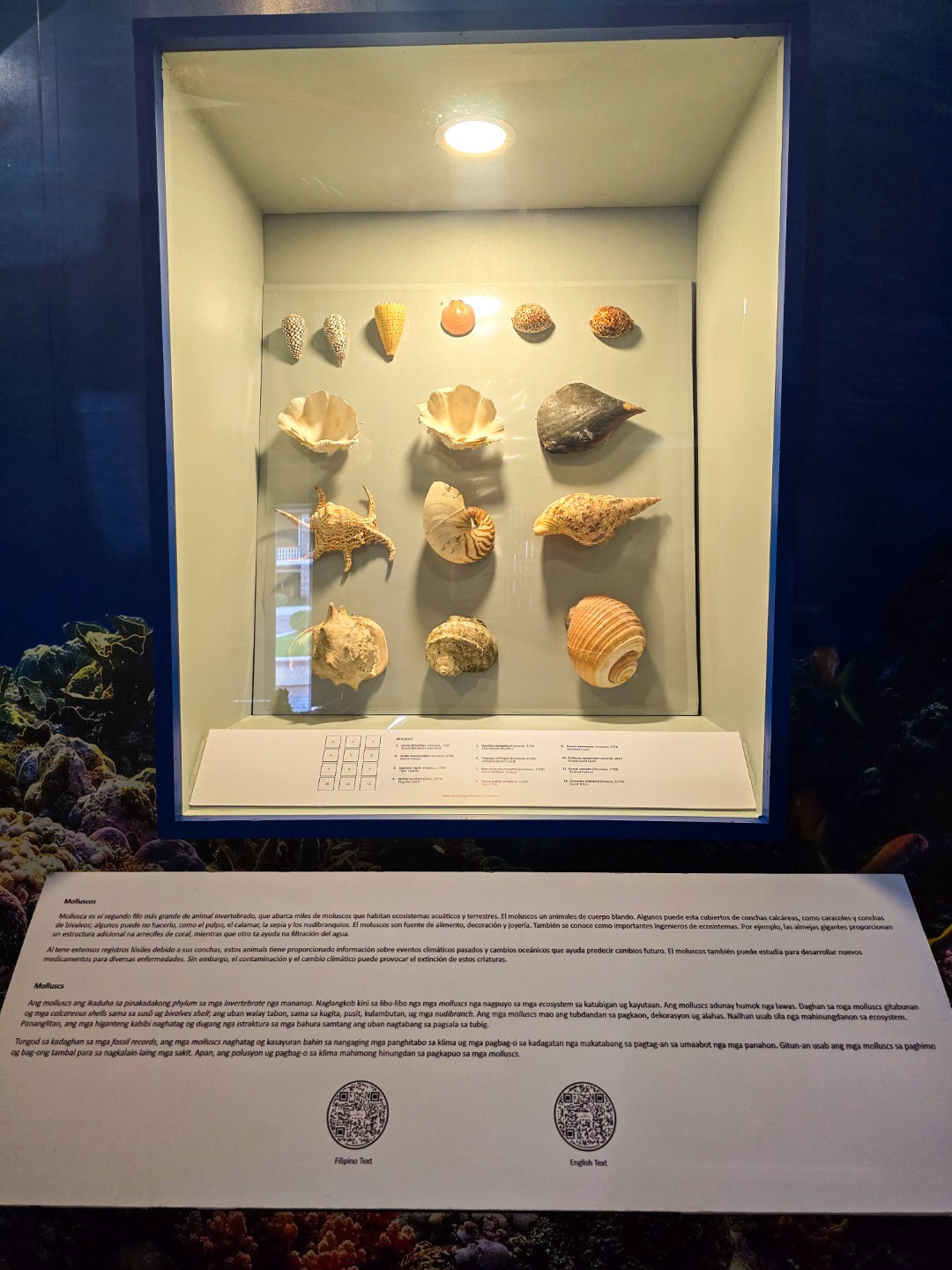

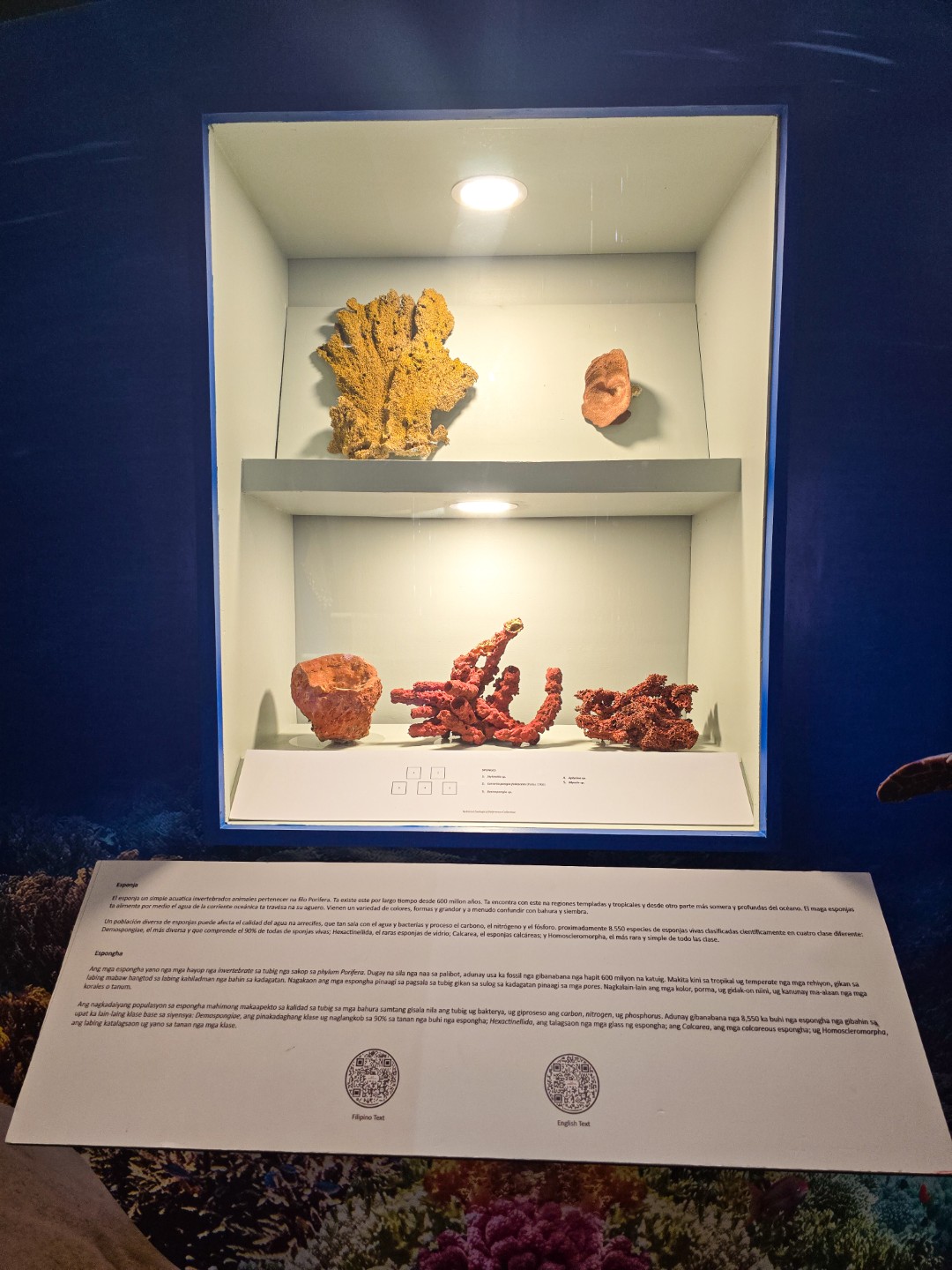

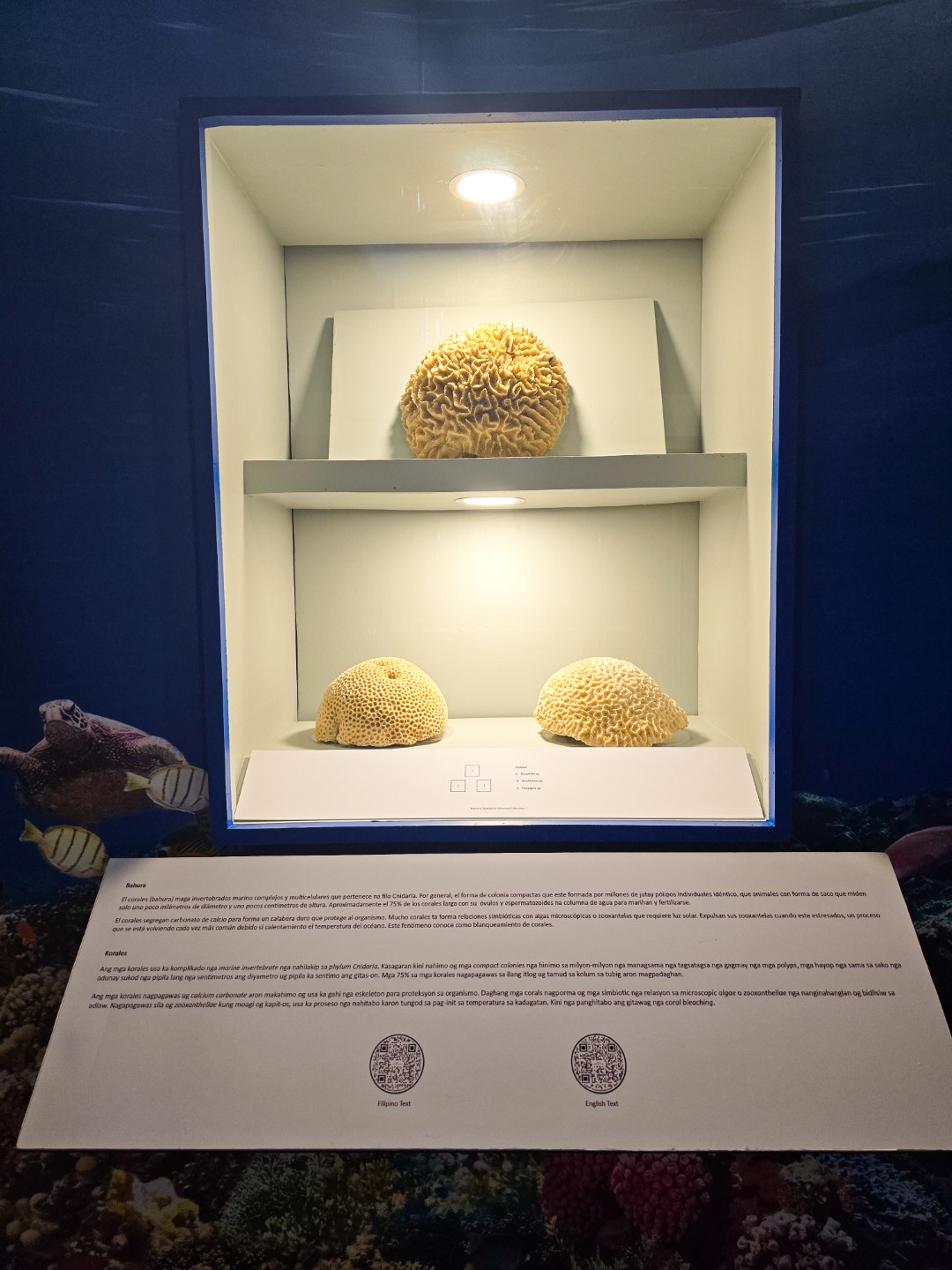

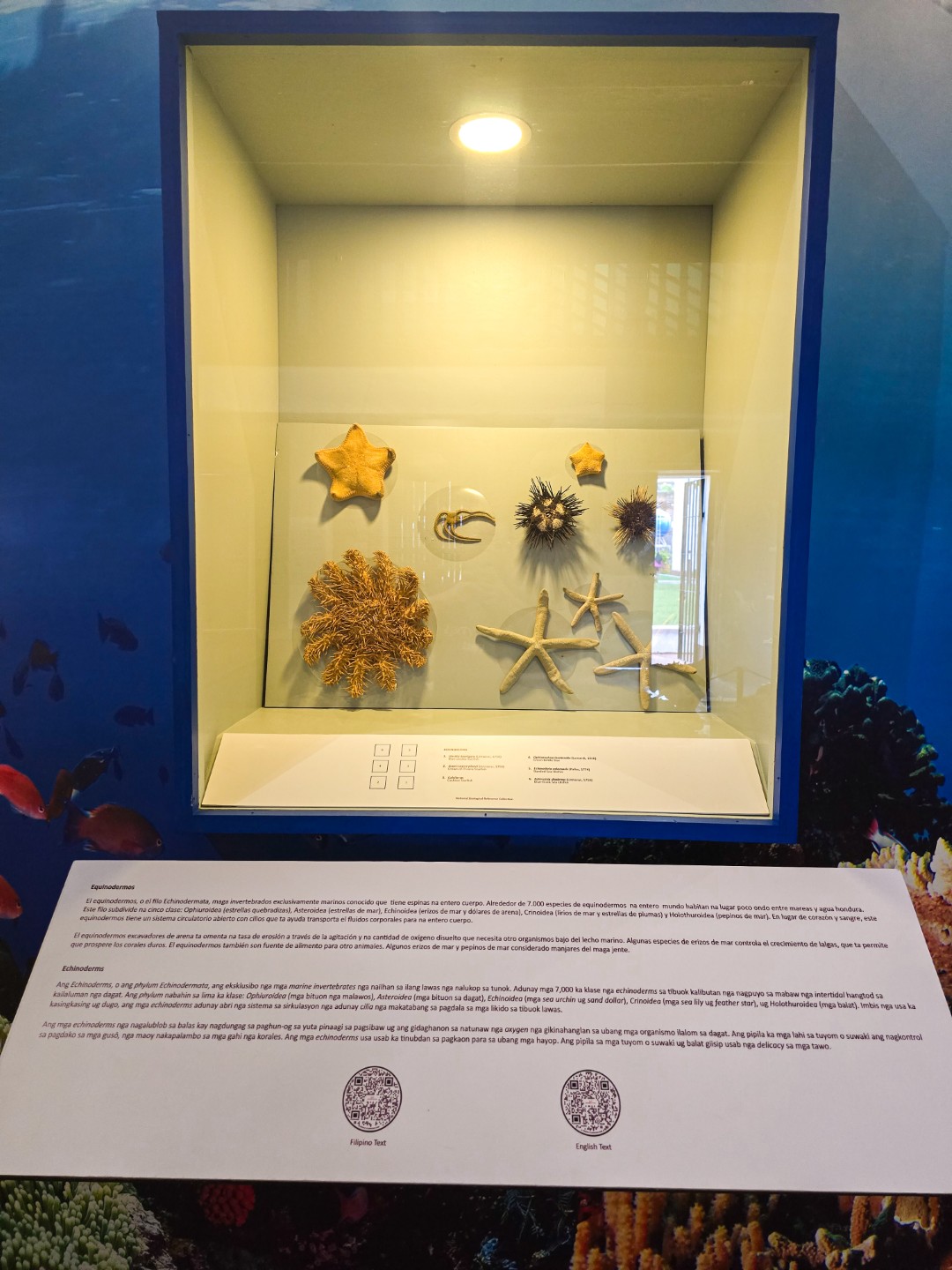

Our exploration inside the museum started in its main exhibition of the natural resources of the Sulu Sea, featuring various species of marine life specimens that can be found in the major body of water surrounding the peninsula and the three island provinces of Basilan, Sulu and Tawi–Tawi.

The Underwater Jewels of the Sulu Sea exhibition, NMP – Zamboanga.

Preserved specimens of sea creatures found in Sulu Sea.

Apart from the natural resources if the sea, the exhibit also features indigenous maritime vessels, such as the vinta and the leppa or houseboat of the Sama–Dilaut. The boats do not only pay homage to the seafaring culture and identity of the inhabitants of the peninsula and its neighboring islands; they likewise provide a window to the ingenuity and resilience of those people who were able to make the most our of their surroundings, no matter how hard and hazardous life at sea can be.

The different indigenous sea vessels on exhibition in NMP – Zamboanga in Fort Pilar.

With the exhibition of the culture and life at sea comes the ones of those who settled on land. Mostly influenced by a mix of indigenous Islamic customs, the exhibit showcases different pieces of clothing, house ornaments, ceremonial pieces and agricultural equipment.

The rich collection of vestments, household and agricultural items in the museum.

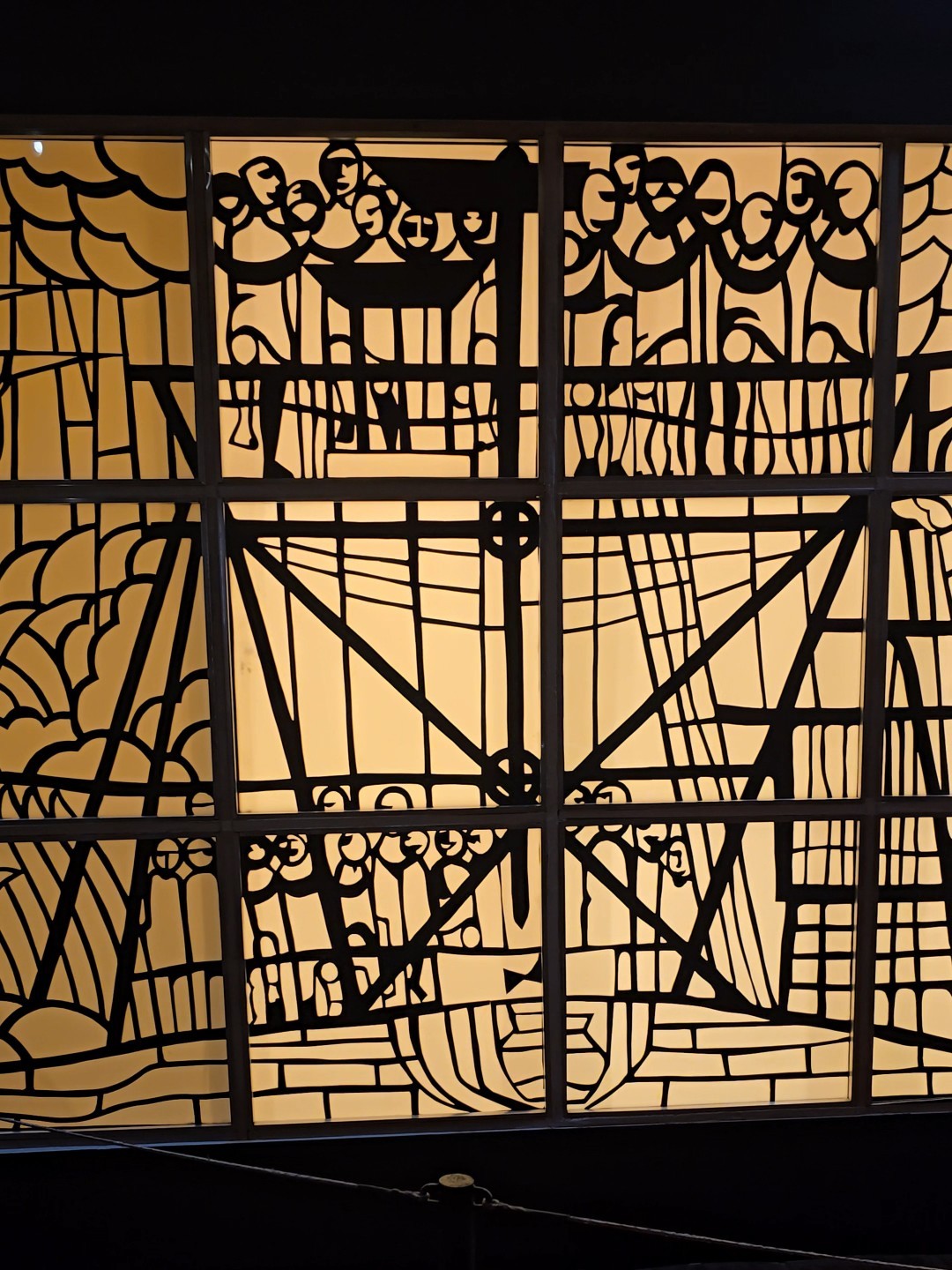

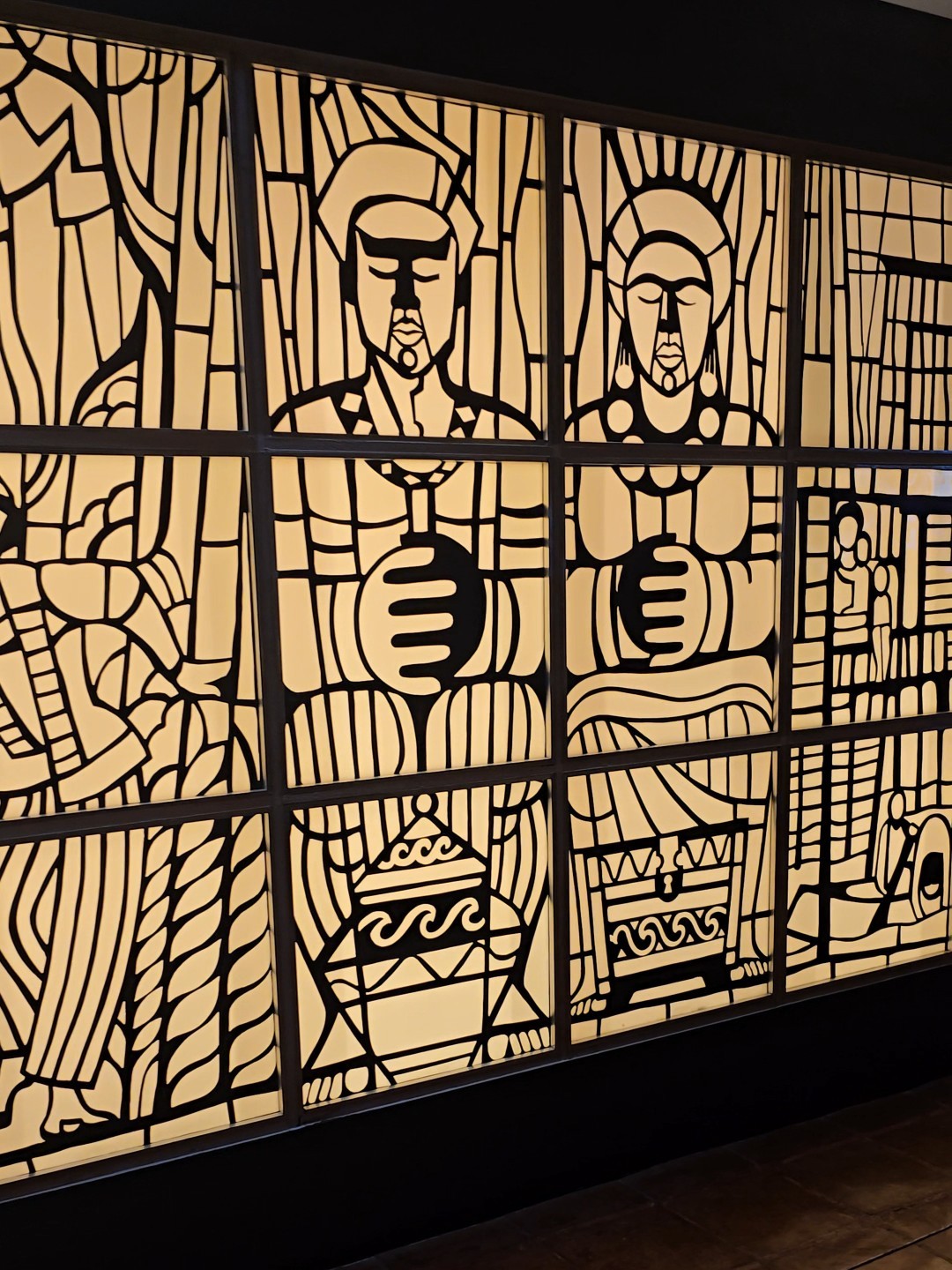

Another interesting piece in the museum was the backlit installation by Noel Escultara, a former curator of the National Museum, featuring the cultural traditions of the Subanun, Yakan and Sama–Dilaut. The description in the museum gives an idea of how the artwork was achieved: The artist drew the image on thin plywood boards and divided the drawing into a grid of 36, measuring 61 by 61 cm. each. The cut-out patterns were painted black and individually framed using aluminum with white translucent acrylic sheets as support.

One may not miss the art installation, as it is the most eye-catching piece in the exhibition.

After seeing the galleries, Ran and I decided to move ahead and go see the eastern part of the fort. Besides, it was already a little short before 05:00 PM and the museum was already about to close. The eastern part, while still part of Fort Pilar, is accessible independently from the museum compound itself, as it keeps an open grounds for those who would want to seek spiritual refuge.

Our experience in Fort Pilar gave the familiar feeling of seemingly being thrown back through the ruptures of time, able to see how things were from the present perspective. It was a similar feeling to when we were walking through the streets of Vigan, or when we were exploring the ruins in Apayao. Somehow, history indeed has its way of manifesting itself, not just in books and in artifacts and relics of the past. It has its way to touch the consciousness of man.

It is that nostalgic feeling for a place and time that one has not yet been to. John Koenig calls it anemoia. I would not coin a term for it, but it is a form of anamnesis that is able to get into human consciousness; one that propels humanity not to forget its historical roots, making history unalterable and unerasable.

Leave a comment